Integral Politics is many things to many people – maybe that is inevitable, given the many perspectives it acknowledges. However, there seems to be a clear distinction between thinking about integral politics as a ‘new political process’ and, more simply, as a ‘way of looking’ at what is already there. The first can be experimented with in the current context of politics, as a new party competing for attention and hoping to infect the broader field. The second starts elsewhere, hoping to work with the raw material of society to generate a different idea of power itself.

The following essay looks at both of these entry points and explores how they can complement each other.

Over the last 20 years, since the birth of the internet, all cultures and structures have been up for grabs. Anyone with a device can get access to information previously exclusive to elites, as well as mobilise others to create movement for change. After a generation of very little change to the post-war political settlement, there has been plenty of experiment.

As I (Indra) write from my home-desk in London, it’s week 10 of the lock-down prompted by the Coronavirus pandemic 2020. Never before have we experienced such a sustained personal, communal and global liminal space. In which time both slowed right down for half the population and speeded up unbearably for the other half. As usual, the least privileged have borne the brunt of the emergency – whether by being pushed to the front lines like soldiers ready to die for their country. Or losing the little security they had in their jobs, or their freedom to leave their cramped flats by day – sometimes in increasingly vulnerable situations.

Meantime the more privileged had time to reflect, spend more time with their families and notice what they hadn’t noticed before – including, even in the mainstream press, the plight of the worst paid and how much our well-being relies on them. One of the moving memories of this time will be the weekly Clap for Carers, in which people across the UK came out of their homes (maintaining social distance) or leaned out of windows to make visible their gratitude at 8pm every week of the lock-down. In some arenas, the relationship between our busy, consuming lives and the quality of the air we breathe has also been noticed. In some quarters, we’re reading about the direct relationship of our extractive growth economy and the origin of the virus in the live animal markets of Wuhan.

At the same time, in countries around the world there has been a noticeable vacuum of political authority. Leaders reacting slowly to the pandemic have repeatedly been shamed by scientists, civil society leaders and the leisure industry who could see the need to shut down commercial operations much earlier than their governments. In the UK, the behavioural architect of Brexit, Dominic Cummings, has single-handedly broken the very fragile contract to stay home that had been brokered across the UK, by ignoring the rules himself.

By contrast, there has been a lot of acclaim for those leaders who managed to keep the pandemic under better control. As one article put it, New Zealand PM, Jacinda Arderne, whose leadership resulted in the lowest infections and deaths per million of population (4, 12 in total) has emerged as “the new leader of the free world”. Many articles noted the success of female leaders in particular, citing Tsai-Ing-wen of Taiwan (6 deaths), then Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Germany.

What was very noticeable in the absence of strong, caring leadership in the UK, was the spontaneous rise of very efficient neighbourhood groups that self-organised to do the work that the state - local councils - could not. Covid mutual-aid networks appeared overnight, often with thousands of names signing up to help bring shopping, medicine and child-care to the vulnerable. Not just the old, but also those with pre-existing conditions and weak immunity.

Next week we are moving slowly out of lock-down – but will anything have changed? Newspapers are encouraging the masses to go back to shopping as quickly as possible – as if it were our duty to revive the national economy. But will we instantly obey? One Sky News report found that only 16% of people wanted to “go back to normal” after the lock down (ref). But this is not an issue that we will have a vote on and, anyway, there is no simple binary - Yes/No or Right/Left question that could capture this complex moment of shifting authority and agency.

Once again it is clear that people have very little opportunity to engage in the design of their collective future. There is next to no architecture for the kind of participatory design work implied nor any clear constituency for action. Are we talking here about social or political responsibility and agency? Where is it located, how can it have purchase on our collective outcomes?

These are not new questions. Most of us have been grappling with questions of socio-political agency for decades. Yet here we are in 2020 facing three existential crises that threaten our very existence: a global crisis of environmental degradation, the national crises of social division and the personal crises of well-being. The human race is not standing proud right now.

Over the period 2010 – 2017 I was part of a progressive political think tank, Compass, serving on the management board from 2015. Founded by Neal Lawson, Compass originated as key consultants to Tony Blair’s Labour government. In the mid 10s, Compass moved to embrace a broad left position – the progressive alliance – after Blair ‘betrayed the Left” with his free-market capitalism and the Iraq War.

However, I always felt somewhat on the outside of the political discourse. As a psycho-social therapist, soft-power consultant, Buddhist integralist and (devoted) single mother at that time, I was always frustrated that there was so little acknowledgement of the complex – bio-psycho-social-spiritual - human being at the heart of society. Where I saw the development of individual as well as collective human agency as the core of any political project, politics described ‘people’ as homo economicus, needing primarily a job and a roof over their head.

While the implication from Maslow’s hierarchy is that once that is sorted, the rest of human potential can unfold, it hasn’t turned out that way. Instead we have been kept in thrall to material needs and have never built societies in which everyone can accumulate the social and cultural capital that gives rise to individual creative autonomy across the board.

Only 2% of people are members of political parties in the UK – up to 5% across Europe. In a paper I wrote for Compass “Is the Party Over? Or Is It Just Kicking Off?” in 2016, I looked at the many reasons why people don’t join, and posed these questions:

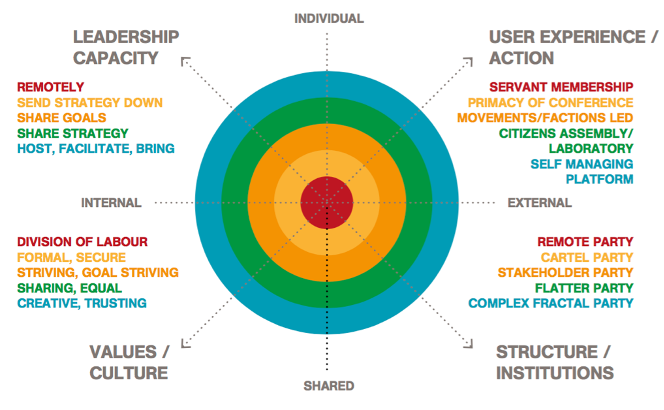

- User experience and action: What does it mean to be a member of a political party? What are people prepared to do as activists, citizens and party members? What kind of spaces can parties meet citizens in, with what purpose? How does an ideal party intervene in the space for political action?

- Structure: What kind of party structure allows a productive connection between vertical and horizontal distributions of power? Where should the initiative arise, and decisions be made? Who manages the polity?

- Culture: good society? What values must be upheld among activists and party members? What behaviour is ‘good’? What is the role of ideology or indeed, philosophy?

- Leadership: What skills and capacities are required to both attract and sustain momentum at all levels? How do we examine and assess the pros and cons of charisma?

It goes without saying, that the general consensus in the UK at the time was that politics was no fun, offered minimal agency to its members and did not model the changes we want to see in society. I myself had stood to be an MP: while I enjoyed every minute of meeting people, the internal party politics was cold and instrumental. Politics was spending all our democratic capital without getting any results – the people on the doorstep knew that. There were no political heroes: even Obama was moving into the zone of ‘ineffective charm, possibly dangerous’ that Tony Blair fell into.

However, at the same time, we saw a lot of political experiments happening around Europe. Syriza in Greece, the Pirate Party in Iceland, Podemos in Spain, Five Stars in Italy, Alternativet in Denmark. They all had political entrepreneurship in common: possibly because many of the initiators had been part of Occupy who had managed to establish their new narrative of the “99%” in just two weeks of remarkable global activism.

Nevertheless, each new party was distinct. Syriza made a huge leap into citizen-led politics, but without any clear vision of how it might manage the European context. The Pirate Party became the party of ‘liquid democracy’, putting its faith in digital participation. Podemos was built directly on the 15-M circles movement, but had no sociocratic structure to keep the two connected. Five Stars was an unashamedly populist initiative with a famous comedian as its leader. Despite new mechanisms for participation, all of these – bar Alternativet – held onto traditional leadership roles within their respective Parliaments.

Each was addressing citizen participation in a slightly different way that might be plotted along a developmental continuum. At one end the servant membership of a party that only offered ‘getting the vote out’ on behalf of the policy making executive’ as an action. At the other a direct relationship between local decision making and national policy. See my attempt to map this against Wilber’s All Quadrants All Levels integral system below, where I have taken the internal aspects of a party to mean its leadership style and shared culture. None of these new parties dropped neatly into one, coherent meme, but all showed varying degrees of development in the idea of citizen agency.

For more on this, see Is the Party Over? Or is it Just Kicking Off?

Alternativet, Denmark

Where Alternativet was radical – and from an integral perspective, teal – is that it entered into Parliament without a manifesto or political programme (see the above contribution by Uffe Elbaek in this issue). Instead they opened political laboratories around the country to crowd source both. The immediate offer was that towns, cities and local communities of every kind, were themselves whole systems, capable of self-organising. Not waiting to be directed from the centre, but ready to feed back to those with power and resources, what was needed on the front line.

Leader Uffe Elbaek, who had directed the global youth training programme Kaos Pilots for 20 years previously, held the development of individual capacity at the heart of his political project. Not simply understood as traditional knowledge and qualifications, but the ability to be creative in the face of the constantly changing reality of the 21st Century.

As leader of Alternativet, Uffe believed in symbolic action to disrupt political culture, sometimes appearing in public in a tutu. He disrupted the political discourse by refusing to answer questions, or admitting ignorance. His followers partied hard and held political gatherings as if they were circus events. The media labelled them clowns but they were anything but: check this Lars Von Trier influenced party advertisement which calmly delivered their serious intent while doing cartwheels.

The early manifesto described Alternativet as a radical Green party with 6 values: Courage, generosity, empathy, transparency, humility, humour. Its purpose was to align the health of the individual with the health of the planet via the health of the communities: I -We – World. All of the above suggested the first teal party, ready to hold and serve the self-organising diversity of the people. In the first two years, Alternative became the fastest growing party in Denmark, winning ten seats in Parliament and several mayoral posts at its height.

Alternativet inspired a number of sister projects across Europe. What follows is a personal account of this journey and the learnings along the way, written by Michael Wernstedt, a witness, a co-founder and a former party leader of Initiativet, the Swedish counterpart of Alternativet. It includes input from interviews with some of the other leaders: Stefan Ekwall, Sanna Rådelius and Tove Winiger. The granular detail is very helpful for understanding what motivates – but also challenges – citizens as we move to organise ourselves.

Initiativet, Sweden

“In November 2016, a seminar was organised with the theme “Do we need a political Alternative in Sweden?” The organisers, Katarina Björk, (an old friend of Uffe Elbaeck), and Johanna Jönsson, MP for the Swedish Center Party, was inspired by Alternativet (The Alternative) in Denmark in the quake of Brexit and the election of Trump. This was the embryo that created a new political party in Sweden, Initiativet, that would attempt to get into parliament and change the political landscape.

The Embryo

Everyone gathered at the seminar unanimously agreed that an alternative was urgently needed. About one third thought this could be a ‘movement’ that transcended many political parties. The other two thirds thought a new political party was needed to drive this change. This debate between being a ‘party’ or being a ‘movement’ would be something that would come up many times in the years to come. At the time, the will to create a political party was stronger.

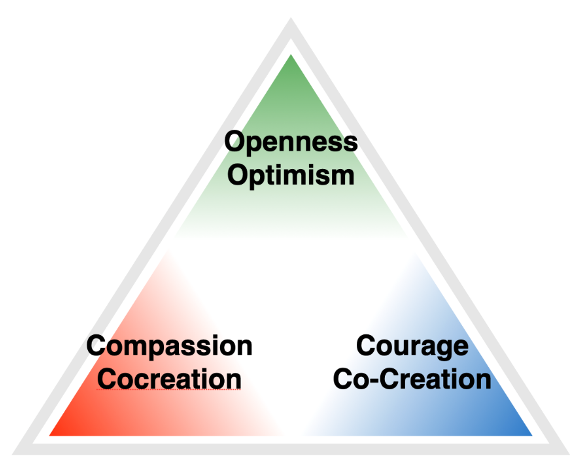

The starting point, in February 2017, was a gathering of around 40 people in Stockholm for a workshop. The theme of the evening was “A prototype for a new political party”, organised by Stefan Ekwall and Ashkan Safaee (who had attended the first workshop in November). We dreamed about what a society would look like guided by, openness, compassion and courage, three of the values of Alternativet. During that exercise, something happened in the room. It was like a breath of fresh air. Finally we could see a new and better world, one that our hearts knew possible. We moved away from the doom and gloom of the news cycle and instead saw the possibilities of another society. And in this group, many of us had found a forum where we could explore those possibilities. It was striking how similar people’s visions were. ‘Values’ became more than fluffy words, but a strong foundation to create something concrete.

Following that workshop, smaller groups started to work on developing the foundations of the party that would become Initiativet (The Initiative): the purpose, name, values, structure, principles, etc. In that process we also experienced what a new political process could look like. A process where we co-create, learn from each other and build on each other’s ideas. This was beautiful and held a promise of what we could build together.

Initiativet started to emerge. The name Alternative was not chosen because we wanted to transcend the current political landscape and include both right and left. Therefore we did not want to be a polarizing Alternative to the current political system but be an inclusive Initiative for a new paradigm.

Building a political Party

Einstein said that “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them”. Hence we knew that we needed to create something new. What emerged was a process oriented party. Instead of proposing finished solutions, we focused on designing the processes that create new solutions.

Much of this thinking was built on the emerging philosophy of Metamodernism. Which in short means that through being able to integrate as many perspectives as possible – from both postmodernism, modernism and traditional beliefs -, we will be able to reach the best conclusion. This is based on the notion that our collective intelligence is greater than any individual’s.

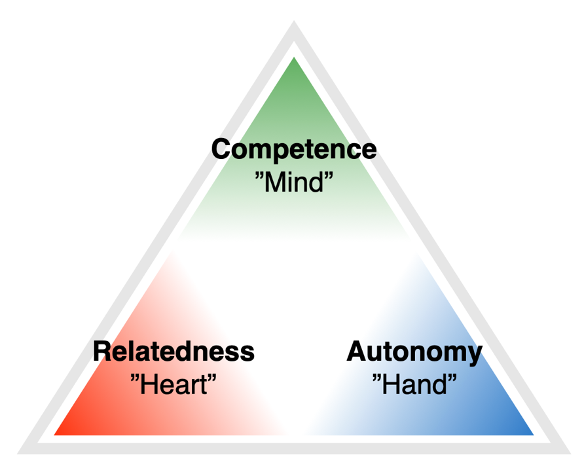

Self-determination theory and the Values of Initiativet

To design this process one needs a framework. That framework was our values: Openness, Compassion, Courage, Optimism, Actionability and Co-creation. These values provided the protector of the general idea. They overlap Alternativet’s values but were adapted to fit the Swedish context. Since we wanted to transcend both right and left perspectives we used Self-Determination Theory's three dimensions (Competence, Relatedness and Autonomy) as a basis for picking the values. Two values focused on Competence (Openness and Optimism), two on Relatedness (Compassion and Co-creation) and two on Autonomy (Courage and Actionability). For the same reason three party leaders were appointed: Katarina Björk, Stefan Ekwall and Michael Wernstedt. The idea was that they would embody the heart (relatedness), the mind (competence) and the hand (autonomy).

Initial leadership of Initiativet

Our vision was “Thriving people on a thriving planet”. To reach this, we would need to create a new political culture. It was obvious that we had three major challenges that we needed to solve: the environment, wellbeing and democracy. Based on our values and these three challenges we invited the public to co-create the political program. This was done physically in “political labs” – workshops where politics were formed –, and online for each of the challenges that we wanted to solve. A process inspired by the Appreciative Inquiry model. The first workshop looked at the challenge at hand, in the second, we dreamed up the ideal situation and in the last, started to formulate solutions. These solutions then went through an “advice process” online where members could give feedback before they were revised and finally voted on.

In building a structure for the party, great inspiration came from the idea of self-organising, made popular by Frederick Laloux’s book “Reinventing Organisations”. That meant anyone could make any decision as long as they had consulted people with expertise on the decision in question, and people affected by it. This is called an “advice process”. The decision to do something is then made in a “consent process”, meaning that anyone can veto a decision. But rather than reaching consensus, the aim of the group is to see if an idea is “good enough for now, and safe enough to try”. This requires a lot of trust from the group and when it works, it is almost a spiritual experience.

In 2018, the decision to participate in the election to Parliament was made through a “consent process” at the annual meeting. The energy in the room was electric, with everyone knowing that anyone could veto that decision but no one did.

Annual meeting 2018

One key aspect of self-organising is the idea of wholeness. How are we able to show up as whole human beings, with our fears, vulnerabilities, strengths and weaknesses? This requires courage, openness and trust. And if we can be whole, we will function much better since we not only use our rational ‘professional’ intelligence but also, our emotional, intuitive, spiritual and embodied intelligence. In short, we will be able to act and interact using our whole capacity.

Many of us had experience from working with self-organisation and had seen the energy and creativity it unleashes. What if we could unleash this energy on a national level, by organising a party this way? Perhaps then we could solve the challenges we were facing! And in doing this successfully, other parties would have to follow: The Tesla for Swedish politics.

In developing these foundations, different wills emerged within the party, and with three party leaders, it was not really clear which direction we were going. The question arose again, are we best placed as a party or as a movement. And again, we choose to be a party. To create more clarity and direction we elected one party leader, and that was me, Michael Wernstedt. This served also as a strategy to break through the noise of the political landscape. With one clear face, it would be easier to appeal to the public than a party with many, or as it may seem, no leaders. In that sense, it was also a compromise between doing something new and innovative and still appearing a bit traditional so that people can relate to, and understand us better.

The Challenge of the Election

In November 2017, ten months before the election, Initiativet was launched. More than a thousand people were engaged, attracted by the idea of creating something new and of solving the challenges we are facing as a society. Local groups formed around Sweden, and we started to develop our party-program through a co-creative process with political labs.

This created a shift from the very intellectual and, to a large extent, philosophical work to much more hands-on practical work. The practical first hurdle was to collect 1 500 signatures to register the party before the end of February 2018. Once that was done, we needed to order, pay and distribute ballots to over 4 000 voting stations that had to be hand-delivered by us on the morning of the election. A major logistical undertaking! Managing to do these practical tasks was hugely successful in bringing us together as a group.

Initiativet’s ballots distributed in one out of 4 000 voting stations.

In March 2018, the leadership was again expanded from one party leader to three, Michael Wernstedt, Sanna Rådelius and Tove Winiger, in order to hold more perspectives. At the same time, a new board was elected consisting of twelve people, seven of which were relatively new to the party and the founding ideas of a process-oriented party. This was a strategic move to be able to appeal to new groups. However, since the idea of a process-oriented party seemed very open, they naturally projected their hopes and visions into the party. Many also brought their experiences from other existing political parties. This created a tension between sticking to the original idea of a process oriented, self-organised party or using the hierarchical structures of traditional politics, to be successful in the elections.

This tension became even more apparent when Obama’s Community organiser strategist, Toby Chaudhuri, coached us on community organising and campaigning. It became apparent that the foundation was not strong enough to dare to do things differently from traditional politics. Not enough people embodied the values and could step into leadership. Furthermore, it became apparent that we were not aligned on the fundamentals. The founders and leadership wanted to stick to the original idea of being a process oriented party, whereas a lot of the new board members wanted to use more traditional ways to run a political party, in order to be successful in the election.

In the end, we did not do a traditional campaign for the September 2018 election. One example of the campaign was a ten-day march from Stockholm to the town of Arboga, where the first parliament was held in Sweden. The idea was to go back to the roots of democracy in Sweden to find what we had lost along the way. En route, we asked people what kind of Sweden they wanted to live in, and we relied on people’s compassion for food and shelter, which created many meaningful encounters.

After the election I left the party. There were two reasons. The first was that I felt that I was banging my head against a wall trying to sort out the internal tensions without seeming to make progress. The second and maybe more important thing was that I, through the journey with Initiativet, had come to realise the magnitude of the challenges we are facing as a society. I came to the opinion that our societal challenges are much greater than what the current political system can deal with. Hence, it no longer seemed meaningful to me to build a party within the current political system, but instead come up with innovations on the periphery that can be adopted by the system later on.

A New Direction

Instead of appointing a new party leader, the time following my departure was used to rethink what kind of leadership the party needed. Following interviews with Sanna Rådelius and Tove Winiger, I share below the new direction for Initiativet.

It became clear that fitting in to the current political media logic was less important than staying true to the core of being a process-oriented and self-organised party. Having a party leader was seen as counterproductive to creating a culture of self-organisation, since a lot of people have preconditioned ideas of what a party leader is and project this onto them. Instead the new leadership was called ‘Catalysts’. Sanna Rådelius and Tove Winiger were appointed as the first Catalysts. There is no limit to how many catalysts there can be.

In this process many people who had more traditional views of what a political party should be, left the party. Many later joined a new party called Vändpunkt (Turning point) that started 100 days before the EU-election of 2019. This was a party with progressive ideas and a more traditional party structure.

The remaining core group of Initiativet thus had the opportunity to slow down and reconnect with the organisation’s roots. Many of the underlying tensions, previously unresolved due to the election rush, were now brought up and dealt with. Hence a new direction started to emerge.

A smaller group, the core, were chosen, that could develop a strong culture to uphold and spread the values and principles when new people come on board. It was apparent how hard it was to act from a new paradigm when being so embedded in the current one. Especially when operating in the current political landscape. Hence the new goal was to embody the values and the culture before building politics onto it. This included redefining what success looks like and to deal with fear of failure. Instead of being lured into the traditional story of success, experimentation and learning started to be seen as values in themselves.

One crucial aspect is to develop the trust, agency and skills necessary to co-create. Developing political self-leadership is now the paramount focus to create change. Initiativet’s role is to create an arena and a culture, where people can develop as whole beings as part of a context and test their political ideas. Further, to create experiences that strengthen and challenge people to become responsive and mature individuals. The purpose is to create and inspire a listening political culture, a deeper understanding of the complex challenges facing humanity and a society that is better for humans, animals and the planet.

The Learnings

From the perspective of the author, many learnings emerged in the three years that Initiativet has existed. Here are some of them:

- A strong leadership is needed that holds the foundations and builds a culture around it. If a movement is opposing something, like #metoo or Extinction Rebellion, it is easier to be decentralised. When one wants to initiate an alternative system however, one needs a more centralised leadership to pave the way and safeguard the culture. Ideally this can be upheld by many people but they then need to be aligned.

- The second tough learning is that it is hard to change the political system from within. It is almost impossible not to become part of the system instead of changing it.

- Third is the importance of embodying the culture. This might make things slower initially but it has to be allowed to take time.

- Finally it is overwhelming and hopeful how many people want to get engaged and dedicate time and energy to change the political system.

See also the story of Initiativet as told by Sanna Radelius.

The Future of Politics?

Initiativet started as a prototype for a new political party. During the last three years we have done a lot of prototypes and learned a lot. The current phase is a step away from traditional party politics to explore and embody what a new political landscape, with a new political culture and ultimately new political structures, could look like. A political landscape that is designed for humans and where we can show up as whole human beings”.

The Alternative UK

While we (in the UK) share, pretty much, all the intentions and reflections that Michael described above, the opportunity that Alternativet presented for the UK looked different form the outset. Uffe Elbaek and I first met at a Compass conference and connected immediately on the new political offer that I-We-World creates. He invited me to speak at a couple of Alternativet events which gave me the chance to experience the movement first hand. Unlike any other political event I had taken part in – ever – these events pulled on the heart, mind and body. I immediately sensed it could go beyond the 2% attraction of politics as usual. The sense was that, in contrast to engaging people with their mind and their feet, whole people were being invoked and involved. It was their agency that would change everything. No wonder so many young people were coming.

At the beginning I thought about how to add what Alternativet was bringing to the progressive movement I was already part of. But on 16th June 2016, one week before the European referendum that was causing so much anger and social division in the UK, I changed my mind. It was while I was on the island of Bornholm, just off the coast of Denmark, at a political festival that I heard about the death of MP Jo Cox, who had been murdered by a Leave voter for standing for Remain.

It became clear at that moment, that it doesn’t matter how good your solutions are. Or however fair and just your democratic aims. As long as you are not working with the people on the ground, using their language and engaging them in the process of decision making, they will be vulnerable to manipulation from outside forces and your ‘good’ project can be sabotaged.

Uffe Elbaek on stage at Folkmodet, Bornholm 2016

Progressive politics often understood and described ‘bottom up’ politics as somehow impoverished, needing power to be devolved from the top to have momentum or even meaning. The culture was, in integral terms, first tier: permanently engaged in a zero-sum game of winners and losers in the battle between parties, even at the local level.

We saw it more as political blindness: unable to see the multiple levels of agency that, if better understood, could be the foundation of a much more evolved democracy in every community. One that would be capable of responding to the multiple crises ‘at home’ far more effectively than the current system. Rather like the neighbourhood nursing organisation, Buurtzorg, described by Frederik Laloux in Reinventing Organisations, we saw the potential of self-organising in towns and cities as key to a new politics.

In Denmark, on that day, the tragedy of our polarised, emotionally triggering political mind-set had come to a head and I jumped ship.

Back in the UK I joined with Pat Kane – writer, musician, curator, political actor – to initiate The Alternative UK and we invited seven network leaders that between them covered the cutting-edge range of initiatives between I-We and World.

- Personal (bio-psychosocial-spiritual) development (Perspectiva, Human Givens psychosocial therapy)

- Community innovation – cosmo-local civil society (Transition Towns, Commoning Movement)

- Political agency for every individual (Flatpack Democracy for Independent politicians)

- Re-imagining global relations (The Good Country Index, Soft Power Network)

- New economies – mostly 4th Sector (REConomy Centre, Social Enterprise Network)

- New structures of feeling including the arts and culture (One Taste)

- Futures – seeing technical innovation as solutions more than problems (London Futurists and the 4th Group)

We imagined that if these could integrate in some way, over time, we would be pointing at an alternative socio-economic-political system.

However, it was clear in the UK that starting a new political party would be a trap. Our first past the post system would prevent us from winning any seats until we had a movement of people that could challenge the dominance of the two main parties. Even the Green Party in the UK had only one seat after 12 years of trying. We had recently watched the fate of the new Women’s Equality Party who had massive cross-party support, but no seats anywhere. Only a familiar, growing frustration with an established media that brings the same frame to every political action.

Instead we adopted Buckminster Fuller’s idea that instead of fixing the old system we should build a new one that makes the old one obsolete. That may sound grandiose, but simply stepping outside of the 2% bubble, it quickly becomes clear that this work has been going on for decades but it lacks a political vehicle to give it coherent, visible and confident purchase on power. We saw the task as threefold:

- Building the new narrative: a new story about Us for the age of people power

- Driving collaboration between those who have been building different parts of a new socio-economic system, to make it accessible to others

- Design and develop containers for the cosmo-local innovation appearing on the ground, in communities. Without containers, all our efforts are diffuse.

With this strategy we launched The Alternative UK political platform on March 1st 2017 in Kings Cross, London. Very much in the wake of Brexit, where the story was of divided communities, families, even friendship groups. Half now triumphant, half in dismay.

Launch of The Alternative UK, March 1, 2017

The Alternative we evoked was not simply a healing of divisions, but a re-orienting of where the story of Us comes from. A transcendence of the current political binaries, towards an idea of people coming together in the communities in which they live – connected to groups doing the same all over the country - to face the real, long-term triple crises together. Using theatre, music, food and drink, our hope was to create a new political feeling – or sensibility – to take us forward.

Over three years, the work has been arduous but rewarding and ongoing – but possibly coming to a head through the Coronavirus.

We began, like Alternativet, by running political laboratories. Working with a petition platform called 38 Degrees – the UK version of Change.org or Avaaz – we had immediate access to lists of people around the country we could call upon to come and give their views about the current politics, and begin to source an alternative.

We had some great events but soon found ourselves playing into the same pitfalls as the old politics. For example: why ask people what they want without any machinery for delivering on their goals? We quickly became aware of the cynicism around anything political. People feeling instrumentalised by power, crafting messages of engagement that led to nothing.

At the end of the first year, we began to craft more thoughtful collaboratories which implied, from the word go, that whatever was discussed at these gatherings would indicate the power of communities themselves in the delivery of the goals identified. Working in a town or city, we began to see ourselves as convenors of cosmo-local power, rather than recruiters to a cause.

We identified a number of movements and places that had already been doing this work for some time and considered joining up to see what that might lead to. For example, the Permaculture movement or Transition towns in Totnes where there was an established I-We-World culture and practice, but next to no interest in party politics. However, it was not – and is still not – easy to introduce a new idea of politics without repelling those who hate politics. Why would they risk all they had built to become part of the severely compromised political culture? Their friendly, arms-length relationship with the local council suited them well. Even so, Brexit did show up the limitations of these relationships. While most of the communitarians we spoke to were Remainers themselves, the towns and cities had mostly voted Leave.

So we moved from Totnes down the road to Plymouth, a working-class city with a nuclear naval base. Also known for being the last port of call before the Mayflower set off with Christopher Columbus for what would become the United States of America. It was here that we co-created the design of our collaboratories. The aim was to bring people together to re-imagine the future. Then build the mechanisms and infrastructure to deliver that autonomously, in partnership with, rather than supplicants to, the council or municipality.

With integral ‘eyes’ we knew we had to go beyond the party political system and begin to think of the citizens as a whole entity with multiple levels of agency. If we could curate groups of those with resources and those with a deeper understanding of the real character of the community into a common vision of the future, we imagined new energies would arise.

We began with what we call “deep hanging out” in the city for some time. This way we became aware of three categories of people, all important in bringing a community together:

- hose who were already doing the important work of bringing the community together. Existing civil society but also social enterprise, leisure groups and sports networks etc. We called them the (amazing) usual suspects

- Those who share the values of the usual suspects but were excluded from their conversations through culture, capital and location

- Those who don’t explicitly share the values and don’t think about participation

By spending time with the ‘usual suspects’ first, we avoided reinventing the wheel in Plymouth. As neutral observers we were also able to see where collaboration could but wasn’t happening. We could also cross-pollinate networks with other towns – even from outside the UK.

Many of these civil society organisations were already connected to excluded communities as their service clients, but had nowhere to be in a creative conversation with them. There were also many communities not implied by their work, who existed almost as islands within the city. For example the naval base or the hospital workers, each of whom had their own social scene and narrative.

Working assiduously to meet and experience the world of those outside the usual suspects, we built up relationships and the beginnings of a trust network that we could invite into our first event which we called a Friendly. With a little bit of funding from the Guerilla Foundation, we were able to offer a meal from the most popular vegan restaurant in town. The local BBC radio station interviewed me in the morning and described it as “the politics of free food and drink”. It was a hit.

Over 120 people turned up to meet each other for the first time. With careful facilitation we were able to have gentle, whole room conversations that allowed it be both intimate and shared at the same time. Through inviting just three very short introductions to the most exciting innovators in the room, we were able to keep it local but also aspirational. Instead of local meaning small or flat, if felt as if everyone was connecting to a system, something more than the sum of the parts they represented.

AUK’s first collaboratory in Plymouth

With their permission, we started a Facebook page where everyone could connect and exchange. Then we planned a second event called The Inquiry. This time we invited local arts professionals of all kinds to design and facilitate a whole day event re-imagining of the future for Plymouth. This side-stepped the difficulty described above, of meeting to discuss current problems that the council was already tackling, without the resources to make a difference. Thinking about the future called on people’s imagination – a resource we are all born with.

This was not simply blue-sky thinking and dreaming. Working with huge floor sized maps, we encouraged people to draw connections between existing projects, plot new transport routes, imagine new high streets or spots for growing food. Again, having a mix of social entrepreneurs and regularly excluded people in the same room, revealed possible new local markets as well as the skills to develop them. Most importantly, we were generating shared vision – that could be both felt and planned.

An invitation to Part 2 of AUK’s collaboratory: The Inquiry

The third meeting was called simply Action and intended to make concrete some of the ideas that this community of trust was articulating. This time we invited an established local network to run the event, which may have been a mistake: they already had a clear vision and agenda which they were not ready to see challenged by this new influx of collaborators. Nevertheless, it was very fruitful and stayed grounded in real, do-able initiatives.

These ranged from:

- Designing local energy hubs

- Food growing and selling eg creating a supermarket for local produce

- Reclaiming empty buildings to provide space for meeting, talking and working together

- Beginning a festival / choir / theatre project

- Starting a new local currency that paid youth work with excess produce such as free cinema tickets, food or transport

- Social enterprise hub and investment club

- Starting a local learning club

But it wasn’t until we were on our way back to London that we really saw how that growing body of work could make a step-change into a new political logic. Through doing this system building work in a town or city, we could build a ‘constitute’ – an informal construction that would invite membership from anyone and everyone in the community. Even those that didn’t come to the collaboratories could be enticed to join through services and events on offer.

Once it reached a good size, the constitute – which we subsequently began calling a Citizens Action Network (CAN) – could invite decision making of all kinds. From participatory budgeting of money raised or deciding on the design of a public convenience. Over time, members of the CAN might decide to get together and – like their counterparts in Frome (where a group of non-party citizens came together to take over Frome town council) – stand as independent politicians to take over the council.

Whether that appealed or not, the CAN is an effective container for people power. As a prototype, it could be easily copied or adapted anywhere. For us, this was the first sighting we had of what might be later described as a ‘new political unit’- the first bit of architecture in an alternative politics.

While this was happening in Plymouth, another major movement was taking shape on the streets of London. In April 2019, Extinction Rebellion – a global protest against the inaction of governments in the face of the climate crisis – stopped traffic by blocking six bridges including Westminster. In a strange premonition of the Coronavirus, this global capital suddenly ground to a halt. The busiest commercial hubs such as Oxford Street, became pedestrian enclaves, with sleeping bags and tents replacing lorries and taxis.

I had met Roger Hallam – Co-initiator of XR with Gail Bradbrook - five years earlier. Although I had previously seen myself as aware and committed to the environmental cause, Roger woke me up. He had a direct connection to the causes and effects of climate change through his own failed farming business, which he coupled with an intense study of the potential of movements to catalyse change. I also knew Gail from my involvement with Transtition Stroud. The story of how Roger and Gail met and agreed to work together is legend.

I bumped into Gail again on the streets during the uprising and agreed to support the development of People’s Assemblies (PA) – XR’s (and previously Occupy’s) mode of radical, inclusive citizen participation. While the method and practice was ‘revolutionary’ in that it consulted ‘the people’, there were few mechanisms imagined for taking the ‘will of the people’ any further. Once the list of demands was made, the groups would turn to the government to get them met.

In many aspects, the expectation was, from an SD perspective, that the majority of people were ‘red’, needing above all to get their voices heard. The leadership was ‘orange’, largely strategic, manoeuvring for power. Meantime, the activists were largely green: emotionally bound up in the equal rights of everyone’s voice to be heard.

Soon after joining the PA group, I joined with Paul Thistlewaite and Sam Weller to start an offshoot that was aimed at community development outside of London. Again, it was our sense that communities outside of London would be less interested in protest and more in the development of their agency, to build resilience where they lived. Less interested in building power, more interested in taking action for their survival – and later flourishing – of the home.

In addition, rather than appear singularly as a climate protest movement, we saw a need to identify and work together with those already committed to the environmental cause alongside those working for well-being and a new economy. Surely, if everyone could have their voices heard, would we choose to save the people and the planet?

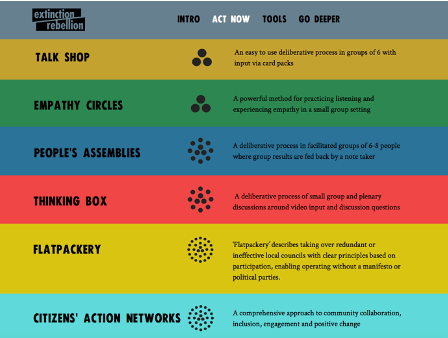

We set up the Future Democracy Hub (FDH) and developed it as a toolbox of processes and methods that would help us reach XR goals, through empowering people in their communities. Many were well-tried facilitation tools, like Thinking Box, or Talk Shop. Empathy Circles provided a great starting point for any gathering. The collaboratory process and CANs were seized upon as longer term visions of community agency.

AUK co-creates XR’s Future Democracy Hub

For the Alternative UK (AUK) it was a chance to work with the 260,000 people signed up to XR – to share our accumulated knowledge and learn from each other. Those that were attracted to the FDH circle were looking for more than the three XR demands on the government, they wanted a full-scale social transformation. However, amongst the large numbers of young people, there was an understandable distrust of the older generation: after all, we had failed miserably until now. I welcomed being led by them in this space and expected to find some clues about the way forward.

In the meantime, we continued to collaborate widely at the systems level, knowing that any new politics has to be backed up by transformative potential more broadly. As part of a collection of civil society groups under the umbrella name CtrlShift, we participated in two Emergency Summit meetings 2018 and 2019, which drew in actors from across the UK to contribute to this system shift narrative. These were largely co-operatives and Community Interest Companies (CICs) working to establish a 4th sector economy. This implied community wealth building, municipalism, permaculture, experiments with currencies, commoning – each a movement of its own that could see itself as the micro action for the macro shift we are all looking for.

While the personal was not always implied in their narrative, the connectedness of I-We and World was. To some extent – its’ not the whole story - we increasingly understood this distinction as arising from the predominantly male leadership of these grassroots organisations. It was the language of the public space where people are described as citizens or individuals.

In the private, more feminine and relational space, the ‘I’ is more easily identified with a personality, a name, feelings. Routing the social and global transformation right into this space, where everyone can experience ‘the personal as political’ is key.

Alternativet / AUK linking the health of the human being to the health of the planet

As Karen O-Brien describes, moving what are traditionally inner or private values into the public space could be the extra mile needed to make our well-rehearsed actions cause a quantum social shift. For that to happen, the role of women is likely to become far more explicit. While in the global North we might refer to this as a new emphasis on Feminine Intelligence, in the global South it takes the form of educating girls and more women into the public space. I explore that further in an essay on Female Politics, also in this issue.

In December 2019, we convened a group of 30 systems actors in London, with a view to trying to name this new socio-economic-political system. Using the parable of the blind men and the elephant in the room, we wanted to see if bringing our diverse perspectives together would cause the Elephant to become visible. There was probably – on our part – some expectation that a system could come together like pieces of a machine. Yet each of these initiatives were already fractals of a bigger system capable of saving the planet. We already understood the basics of circular and regenerative economics. And just knowing that was not enough.

Instead, in the course of the event, we almost fell out. Partly this was the subtle competition of too many chefs. But most noticeably, it was the result of a constellation exercise in which democracy was invoked. How would we sell our system to the rest of the world? From that perspective, it was clear that we were still very elite in our language and expectations of change. We were not yet embodying the diversity of system change needed, even as it appeared in our towns and cities. Our own way of being right had to change: we should be actively looking for what we didn’t already know.

Around the same time we were invited to be part of Catalyst 2030, a global network of social enterprises and NGOs who were collaborating to see what could be done to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 – a target date that has almost entirely slipped away. In that space, I began to meet more of the mind-sets and actions of countries and cultures I rarely meet on the ground in the UK – although I could, especially living in London.

As evidence of that, I was invited recently by Nat Whitestone, founder of A Fairer Society, who wanted to introduce me to the concept of Neighborocracy. Founded by Joseph Rathinam, this comprises groups of 30 families, each forming their own Neighbourhood Parliament (NP), made up in turn of an adult, youth and children’s Parliament. Each person, at every age level, becomes a Minister for one of the SDGs, becoming responsible for that issue in their neighbourhood.

Sounds like a good game? It is in fact a real time movement of 400,000 NPs based in rural India, with equivalents in Nigeria and Peru. As I’m writing, there is a cohort of UK community organisers, one from Extinction Rebellion about to undertake a training.

If all of this sounds too much like a smorgasbord of initiatives without a coherent logic, that would be wrong. In each case, we have been seeing similar patterns arising in a wide variety of new initiatives – from outside the 2% political bubble - that could, together, add up to a new socio-economic-political system with multiple levels of agency. Not by moving into one coherent whole, but by moving into alignment and becoming better related. Relationality itself is the shift.

So, at this moment in time, The Alternative UK offers three actions:

- A Daily Alternative media that works at changing the narrative about what it means to be human, living in community with a purchase on the planet

- Naming and making visible the Elephant in the room: the new system that makes the old one obsolete

- Building Citizen Action Networks

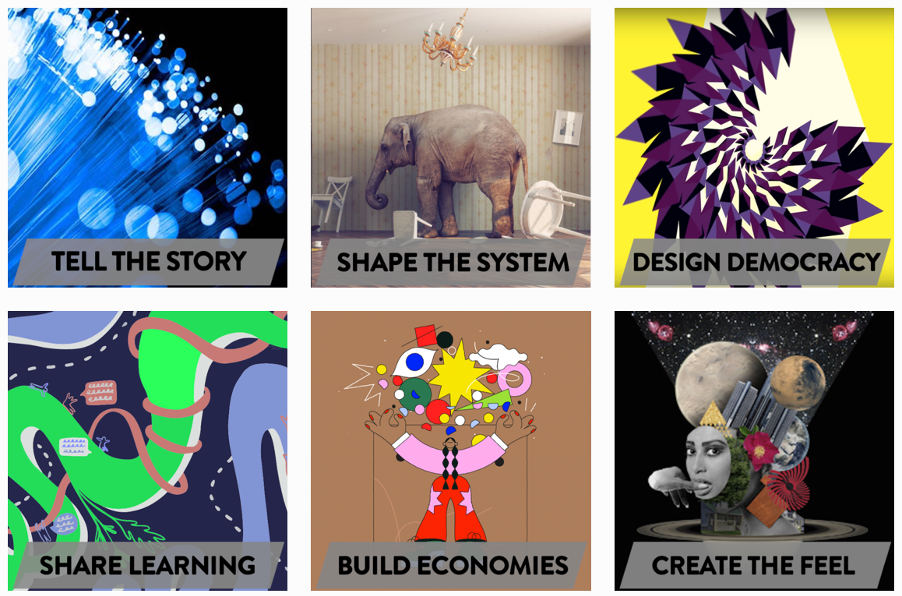

In March 2020, on our third birthday, after three years of participating in others’ projects and sharing our findings, we wanted to offer more participation ourselves. Having observed at least six different kinds of ways of changing politics we offered these entry points for co-creation:

AUK offers six entry points into the question of building a new politics

Behind each one is a decision-making platform to encourage project building. If you join up you are connected with all the research and meet others ready to take action.

When the Coronavirus pandemic arrived, we were ready for the increase in interest from people, many of whom were considering the dysfunction of our system for the first time. But none of us could have anticipated the shared feeling of existential insecurity that was being shared, in the absence of any strong authoritative leadership in the UK (see our editorials on this here).

While the government took its time in responding to the pandemic, significant businesses and institutions – most notably Premier League football – closed themselves down to keep people safe. People at the neighbourhood level in particular, took it upon themselves to self-organise care and shopping for the vulnerable – knowing, from years of austerity, that their local council would be of little help. Every Thursday night, people all over the country, came out of their homes – at a safe distance - to clap the underfunded, misappropriated NHS.

Knowing how quickly people forget the quality of genuinely unexpected experiences, we designed an App called Before&Now which helped people to capture what was changing in their world. How they were feeling different about themselves, each other and the world around them.

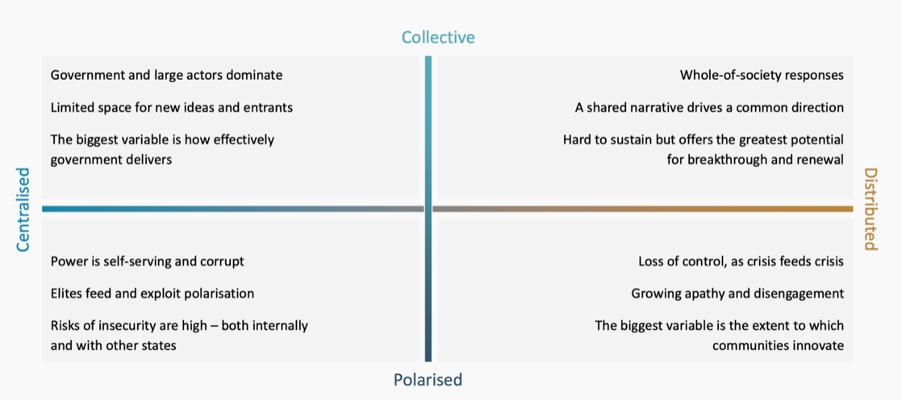

A major charity, the Local Trust, asked us to run our collaboratory on Zoom, for groups of 30 people in lock down around the country. We worked in close contact with the Long Crisis Network who had also produced a report for the Local Trust which came up with four clear post-Covid Scenarios: see below for the diagram and here for the report.

While we found evidence that seeds of all four of these scenarios were present in our communities at the outset of the co-lab, it changed over the three sessions we offered. With only a minimum – though carefully facilitated – engagement between diverse elements of each community, the groups began to cluster their thoughts and actions far more in the top right quadrant. There is a clear appetite right now for stepping up, autonomously, and taking responsibility for immediate outcomes. As one group said, “we’ve had a taste of taking control of the situation, and we’re not going to give our power back”.

Where might this lead us in the coming year? There’s little doubt that the UK and US governments are going to do their best to send us all back to business as usual, possibly in accelerated ways to make up for the time lost. The growth economy, temporarily shut down, must recover. But will they succeed?

Meantime, the call for a genuine alternative is getting louder. In our own network of networks, there is a feeling that, if we hold our nerve, we could now begin to make visible better ways of bringing the health of individuals more directly into line with the health of the planet, via the health of our communities. Precisely because more people are now looking for that.

But it is clear that this cannot be done from the top, within the old political culture which remains, on integral terms, predominantly first tier. While all parties continue to look at each other as competitors, strategizing for prominence in a zero-sum game, there is no chance for genuine representative democracy.

Since the wave of political entrepreneurship across the world began, both Alternativet Denmark and Initiativet Sweden have declined in their popularity with citizens, largely beaten back by the old political culture as much as strategy. It has become clearer that any movement of the people needs its own expression and representation at the regional and national level, independently of political parties. Could that be captured by Citizens Assemblies – maybe as a second chamber of government?

It remains that nothing will change unless there is somewhere for people to participate, to make decisions and build fractals of progress, capable of adding up to whole system change. We think that – in a combination of all the initiatives we have described above – that architecture is coming into view. Cosmo-local Citizen Action Networks (of all kinds) in partnership with independently run councils, participating in the increasingly visible and effective 4th sector, regenerative economy (Elephant) are the foundation. How this works alongside the municipalist movement, national level CANs and Citizen Assemblies, and within the global regenerative economy is becoming clearer day by day.

This year, co-creating with our network of networks, we will step forward with a plan. Watch this space.

Indra Adnan is Co-Initiator of The Alternative UK, a political platforms inspired by Alternativet in Denmark. Her commitment is to networked grassroots politics that release the power of people and communities to sustain the planet and that reconnect people to the local eco-systems of solutions available (I, We, World). She is concurrently a journalist (The Guardian, Huffington Post), a a psycho-social therapist (Human Givens Institute), founder of the Soft Power Network (consulting to Finnish, Brazilian, Danish and British governments), Buddhist, Futurist, School Governor and Mother. Recent publications include Is The Party Over? and New Times, and e-book Soft Power Agenda, available on www.indraadnan.com. Indra is currently writing The Politics of Waking Up: Power and Possibility in the fractal age, to be published by Perspectiva Press this year. She has been co-opted by IFIS to be part of the LiFT Politics team.

Indra Adnan is Co-Initiator of The Alternative UK, a political platforms inspired by Alternativet in Denmark. Her commitment is to networked grassroots politics that release the power of people and communities to sustain the planet and that reconnect people to the local eco-systems of solutions available (I, We, World). She is concurrently a journalist (The Guardian, Huffington Post), a a psycho-social therapist (Human Givens Institute), founder of the Soft Power Network (consulting to Finnish, Brazilian, Danish and British governments), Buddhist, Futurist, School Governor and Mother. Recent publications include Is The Party Over? and New Times, and e-book Soft Power Agenda, available on www.indraadnan.com. Indra is currently writing The Politics of Waking Up: Power and Possibility in the fractal age, to be published by Perspectiva Press this year. She has been co-opted by IFIS to be part of the LiFT Politics team.

Michael Wernstedt is a social entrepreneur working to build a resilient world where both humanity and life on the planet thrive. He has co-founded and served as the party leader for the political party the Initiative, a party which aims to create a new political culture in order to implement a metamodern political vision. He also serves on the board of the Raoul Wallenberg Academy for Young Leaders, an NGO which empowers 10 000 young people to make a difference every year. Michael is a partner of the LiFT Politics project on behalf of SelfLeaders, Stockholm.

Michael Wernstedt is a social entrepreneur working to build a resilient world where both humanity and life on the planet thrive. He has co-founded and served as the party leader for the political party the Initiative, a party which aims to create a new political culture in order to implement a metamodern political vision. He also serves on the board of the Raoul Wallenberg Academy for Young Leaders, an NGO which empowers 10 000 young people to make a difference every year. Michael is a partner of the LiFT Politics project on behalf of SelfLeaders, Stockholm.

Die Medieninhalte und alle weiteren Beiträge dieser Homepage finanzieren sich über Euch, unsere Leser:innen.

Bitte unterstützt uns nach Euren Möglichkeiten – egal ob mit einer kleinen oder größeren Einzelspende oder einer monatlichen Dauerspende.